In the Blog

Accommodating without Antagonizing: Accessibility Is Important

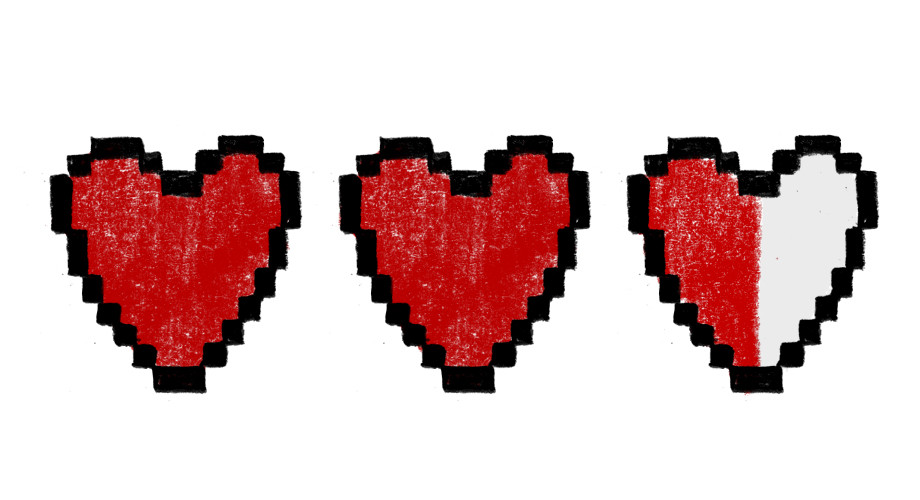

Illustration by Erin McPhee

I was made to feel guilty about my chronic illness and disability when I least expected it. I’d gone to the beach with some friends and had enjoyed a lovely hour playing in the Pacific.

After our swim, we discovered that the closest route to the street was a long, steep, staircase. I couldn’t do that. Stairs don’t work for me these days. I asked if we could find another path, so we walked five or ten minutes out of the way to get to a ramp. I was able to navigate that with minimal difficulty.

One member of our group wanted to detour to visit a store, but we knew it would mess up our schedule. We kindly told her that we’d be happy to meet up with her later, but she declined for some reason. She was seething for the rest of our walk. And then she turned to me: “I don’t know why they have to go out of the way to accommodate you, but we can’t do what I want.”

Boom. She went there.

As much as my friends told me to shake off that comment, I can’t lie: it hurt. A lot. As a chronically ill person I’m painfully aware that I often need accommodation, and I do worry that I’m putting others out. I don’t want to. I try to avoid places where I know for a fact that the situation will be impossible for me.

When I remembered the comment later, I wasn’t sad anymore; I was livid. It made me consider all the times that disabled and chronically ill people are resented and accused of “gaming the system” or inconveniencing others with their requests for accommodation. All the times they’re challenged by those who don’t think they really need assistance. There’s that infamous “…but you don’t look sick!” line. It’s silly of course, because sick and disabled people don’t walk around with neon signs on their heads announcing their conditions, and a lot of illnesses are completely invisible. When I’m not wearing a germ mask and my lips aren’t blue, I don’t look any different from anyone else. It doesn’t change what my labs and medical reports say or the diagnoses I’ve received. I really shouldn’t have to explain this to anyone.

Nobody should be made to feel ashamed or guilty about being sick or disabled. Nor should anyone who needs accommodation feel bad about requesting it. Accommodation is a protected right, not a special favour. Both the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act require businesses and employers to offer reasonable accommodation to those with disabilities. There are some loopholes and exemptions in both pieces of legislation, but the message is clear: those who need assistance should receive it. However, neither law can mandate respect and consideration for the disabled and chronically ill, and thus, there’s oftentimes drama when accommodation is requested. And that’s not even remotely okay.

Disabled and chronically ill people don’t ask for accommodation to piss anyone off, be difficult or complicate anyone else’s lives. They ask because they need assistance.

Accommodating someone’s need is not the same as fulfilling someone’s want.

In the beach incident mentioned above, I needed a ramp because I couldn’t do the stairs. It was that simple. I wasn’t asking everyone to go out of their way because I’d decided I wanted a scenic tour of the beach or I thought that we really needed to walk an extra kilometer. And quite honestly, I would have been fine taking the ramp on my own if everyone else had decided to do the stairs.

The bottom line: disabled or chronically ill people don’t request accommodation for the hell of it. It’s not because they’re difficult or lazy. It’s because they don’t have any other way to safely accomplish whatever the task at hand might be. Period.

Disabled accommodation can be more challenging, time-consuming or costly than doing things the “regular way.”

Many years ago I went to a concert venue that was standing-room only. The accommodation they had for disabled individuals who could not stand was to seat them at tables. The catch? You couldn’t sit there without spending at least $15 on food and beverages and paying a service charge. Able-bodied patrons had the choice of standing or paying to sit at a table. Disabled patrons had the choice of paying or not going to the show at all.

I once worked in a very old theater. The venue was landmarked so it could not be easily altered. The only space available for an accessible restroom was on the top floor, in an area that was never open to the public. In order to get there, one needed to take a private elevator that was also usually off-limits to guests. Therefore, disabled patrons who needed to use the bathroom had to take the elevator up to the restricted area with a staff escort, who waited for them to finish and brought them back downstairs. It was admirable that the theater was committed to disabled patrons enough to add an accessible restroom any way they could, but I daresay that most of us wouldn’t enjoy going through that song and dance every time we needed to pee.

I recently attended a concert at a major venue up on a hill. At the end of the night, those of us who could not handle stairs or a long walk to the shuttle bus bay were directed to sit outside to wait for the buses to drive up the hill and pick us up. They did not arrive for almost an hour. There was simply no way they could have gotten there sooner with all the traffic around the venue.

At a local theme park I love, many rides have separate loading stations for patrons who are in wheelchairs or cannot do stairs. There are usually only one or two ride vehicles for these loading docks, so disabled customers often end up waiting longer than able-bodied ones to board the same ride.

I’m not complaining about any of this; it is what it is. All of the businesses I mentioned above – with the exception of the first – did whatever they could to accommodate disabled patrons. I’m just making the point that those who complain that disabled and ill individuals get “special perks” or “get to go to the front of the line” don’t understand exactly how this all works. We often end up spending double the time and money to do the same thing as an able-bodied person. And that’s really not how it should be, in an ideal situation.

Accommodation allows a disabled person to have parity, not “special treatment.”

Seriously, folks, just stop with this one. When you use a staircase and I use an elevator, we end up in the same place. The elevator isn’t taking me to a special A-list only nirvana. When I took the ramp at the beach, I ended up on the same street I would have accessed via the stairs. Accommodation allows me to do the same things and go the same places that you do, as much as possible. That’s it.

Shaming or arguing with a disabled or chronically ill person will not magically make them able to do the things you want them to do.

A disabled or chronically ill person is the final judge of what they can or cannot do and how much fuel they have in the tank on any given day. Those decisions are influenced by a number of variables, which may include, among other things, their physicians’ recommendations, how much their illness is flaring up, how they’re responding to treatment, or what their current labs look like. Something as simple as a change in the weather can have adverse effects – for me, for example, barometric pressure changes can trigger migraines. Yes, that does mean that someone might have a lot of energy one day and be completely out of the game the next.

I love baseball. When I was at my team’s home stadium one night, the escalator was out of order. I asked an usher where the elevator was located. She could have simply told me. Instead, she argued with me for several minutes, insisting that I could take another, very steep route to the upper deck. She proceeded to shame me when I reiterated that I needed the elevator. No matter what she said or how much she bullied me, it wasn’t going to change my needs at that moment.

Disabled and chronically ill individuals often encounter people who downplay or dismiss their challenges. This often runs hand in hand with that “you don’t look sick” line. We’re sometimes cajoled that we could do things, if only we tried. Who is to say that a person isn’t trying already? I can’t speak for anyone but myself, but I do push to do as much as I can. I fight tooth and nail to keep dance in my life, for instance. Guess what? Some obstacles are still insurmountable or require assistance or accommodation to circumvent. Shaming, haranguing or yelling at me about what I can’t do won’t make those things possible. It will just stress me out.

A disabled or chronically ill person will tell you what they’re able to do. If they don’t, you can always ask. Their response needs to be taken at face value. They know themselves and their bodies better than anyone else, and they need to be believed and respected. Period.

Many healthy people don’t understand how much privilege they have, and it influences the way they treat the disabled and chronically ill.

Able-bodied privilege is an interesting thing: you don’t realize it’s there until it’s gone. The first time someone is seriously ill or injured and they discover just how many common, everyday tasks now require strenuous effort – or how much of the world around them is geared toward the able-bodied in all respects – it can be very surprising. That’s how it was for me.

The famous Spoon Theory describes just how challenging things can be for many chronically ill people. Since I’m an old-school Nintendo geek, I tend to think of it in other terms – the heart containers that Link uses to store energy in The Legend of Zelda video games. Many healthy, able-bodied people have a bunch of heart containers, and thus have enough juice to face most of life’s basic challenges most of the time. I, on the other hand, have maybe three or four heart containers. I’m fighting through Ganon’s dungeon just like they are, but it’s much harder for me to get through the game sometimes. I often have to stop to replenish my energy, and sometimes I get knocked down once too often and have to regroup and start over.

I think that it’s sometimes hard for people with sixteen heart containers of energy to consider what it’s like for those with three. That’s not implying that anyone is malicious or ignorant; just that it’s a reality they haven’t experienced firsthand. And that lack of understanding makes it difficult for them to fully get where chronically ill people are coming from all the time.

Legally, reasonable accommodation is a protected right. Ethically, having respect and compassion for everyone, regardless of health or abilities, should be a given. Not everyone gets this, but it’s something that everyone will need to figure out sooner rather than later. The world doesn’t just belong to those who are able-bodied