In the Blog

She’s Shameless: E.J. MacBain

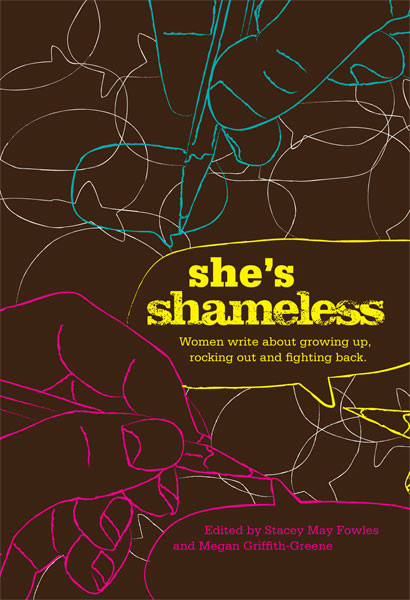

In the weeks leading up to the launch of She’s Shameless: Women write about growing up, rocking out, and fighting back, we’ll be posting sneak peak excerpts from the book. E.J. MacBain is a writer and editor living in the Northeast. Her nonfiction has previously appeared in Hip Mama magazine. She is the proud feminist mama of a toddler son and a baby daughter.

I’m Still Here E.J. MacBain

1982: Roller skates with rainbow knee-highs, braided friendship bracelets wet to the skin, blueberry Slurpees all summer from 7-Eleven, John Cougar cassette tapes of “Jack and Diane,” the secret purple-clad, girls-only club, and threats from the older junior high school girls in the public library, who pretend that Crayola markers are boys’ mini-dicks and suck them to show us: This is what you have to do when you get to seventh grade.

My parents’ divorce, my mother’s suddenly-single freak-out, the parties with her divorcee jet set, and her new boyfriends, boyfriends, boyfriends, while I sat with my friends and wondered about the state of their parents’ love (and sex) lives and why the Girl Scout badges never fit, why I never graduated even from Brownies, and why all the boys loved all the girls who didn’t look a thing like me, Kate, Heather, or Eve with her wicked thoughts and her slumber parties that turned to late-night viewings of the porn channel’s Midnight Blue. What would Prince do? Who was Sheila E., and how could she be so sexy and play the drums? Why was the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue so titillating, and why did my Dad hide it? Were we the only ones who had to hunt so hard for soft-core porn?

Befriend Patty with her red polka-dotted headband and her pink-lined gym shorts with white cotton briefs. Spend every day from fourth grade on with her for two years. Visit her Army-barrack house and her Army friends, with all their toys littering the lawn and her long-haired mother in the dim kitchen with a bowl of brownie mix we dipped our fingers into. Crave afternoons laying in her bed and the way the sun always stayed extra long on our skinny legs with their blossoming thighs. Count the tiny, tiny freckles from her ankle to the crease of her upper thigh–and my, oh my, how we promised to write each other forever when she had to move in sixth grade and then hugged so tight during our last goodbye before the bent-metal front door. We kissed a fraction of a second too long. I touched her hair like it was the silkiest ribbon from a stitched-up Strawberry Shortcake doll.

I love you, I said. I love you, Patty– I love you, too.

The back of the classroom, where I camped out after the divorce. How come I hid out there? Why did I act that way? Blank stares from the teachers who don’t understand why I don’t understand and don’t know why I didn’t read the section, or can’t understand why I just sit and write, but don’t write anything about this assignment–just letters to Patty Strawberry-Shine Hair, Patty Finger in the Batter, and Patty Kiss at the Front Door.

Receive no letter from Patty five months later, but, still, write her every single day. Write all about the way the road just ends at the shore, and how you can’t even imagine getting through a day here. What will happen now that Washington Junior High School is next, and what about the white cotton underwear? Are girls supposed to wear something else now; what is it about the swimsuit issue? Do you remember when we said goodbye?

Go back to the long hazy days. Find out that three girls have given blow jobs already. Say that the purple-clad, girls-only club should only allow in girls that don’t wear tight designer jeans. I mean, really, why do they do that? Remember the scene with Stacy when we played doctor and I made her look at me. No, really look. I asked her to use her stethoscope. And we did that–played–told each other that our butts were sick. Yes, it’s sick; you have to make it better. Touch and kiss. See out the window the cars going by and then remember, it’s now fifteen days to junior high. What will we do?

Remember that Patty still hasn’t written, but that’s all good. I can play doctor here with other girls. See her now on some other horizon–are her friends all tall like me? And do they wear their hair back like I do, in two tight barrettes? She’s having fun with the Hula Hoop and jump rope, and she doesn’t need to think about any of these things, like I do, here in the Northeast. I mean, she’s in West Virginia now. They all picnic and sing gospel or something. None of them play Ms. Pac-Man. Or something.

They all know that girls like Patty and girls like me can only play together without anyone noticing for so long, and then, you know, you have to say something to others about it, or, worse, you’ll be taunted for what you do. You want to tell someone, like your mother. But see, your mother’s in the bedroom now, wearing that slip as thin as a fly’s wing, as slippery as sun-melted butter, and I can tell you, boyfriend number five is like boyfriend number three, except sometimes, somewhere, she comes out and sits with me, and tells me to prepare myself … for everything.

Cry all afternoon in the second-floor bedroom after realizing that Patty will never write back. Hurl old stuffed Curious George across the room and against the wall. Take the last remaining letter to Patty and tear it up for the trash can. Better yet, burn it in the toilet. You can’t imagine what it might mean to look this close at a longing this shameful. Tell myself: don’t look too much, don’t look too close. Remember, it’s not about the girls anymore even; it’s about what you have to offer the boys.

Spend junior high school hiding in the girls’ bathroom during all breaks.

Go to high school, but do it with barely a sound. Call for the boys, but barely make a noise. I said, Hi. I said, Yes, I’m here. I said, No, I’m a friend of Claudia’s. I belong here, really, can’t you see? She’s the sexiest and prettiest girl at this basement-apartment-Jack-Daniels-post-hippie-band affair. Call me whatever you want to–pothead, silent girl, too-tall friend, the one looking too far back to the nineteen-sixties.

Go together everywhere. The three of us: Claudia, me, and Tori. Sexy, Silent, and Athletic. Broken, Broken, and Broken. Realize I can smoke it all till it makes us so silly, can’t even imagine how we’ll drive. Realize, though, that actually a guy sees me, and he plays the drums, too. Can’t you hear this band playing “Dear Mr. Fantasy”? They practise over and over again then pray to the throne of Eric Clapton or Jimi Hendrix. They call this beat-up, Route-8 place the “Red House” and decorate the Christmas tree with empty whiskey bottles, then huddle in the back room for baked-up coke off cookie sheets. Do I look OK? I can’t see so clearly in that bathroom mirror, and the line is so long while that boy cuts and snorts alone. I look OK. Timmy, the drummer, is here now. Wants to show me how he fixed up this old car. Ride with me? He asks. We go aimlessly. All the way to the beach. Slide down in the front seat so he can touch every part of me, and don’t ask about the girlfriend at the University of Maryland or the other one crying upstairs somewhere in the Red House–see how quickly his fingers slide in, but don’t part me all the way. Say, I want to wait, and then wait, every other day, a few more bases, till I can finally–dear, Jesus–let it all go. Why can’t I just let it all go?

Cry for weeks too long after he finally leaves me, then weeks later have to write him that stupid letter: I have chlamydia. Go to the doctor yourself, and tell those other girls.

Try again with the too-skinny, too-scattered Justin, who always seems to have three, four, or five girls handy but is, thankfully, at another high school. We do it again and again, quickly, in his basement room, before he finds another stupid way to insult me. After sex, in the fluorescent-lit bathroom, he laughs at the stray dark hairs sprouting on my chest, and I vow to never open myself up that way with a stupid guy again. Don’t ask them to look at your flaws. Remember, you only look that closely when you’re alone. Remember how, somewhere, Patty is probably taller; remember to think more about the girls.

Stay with Claudia and Tori till we can talk all night, high, about sex. Remember to tell Tori to report our art teacher, Mr. Mitchell, who keeps leaving messages after school hours and telling her to come and meet him in that lot by Saugatuck Road, just to talk. Feel how nice it is to say: I’m not a virgin. Because really, this is what it was all about for so long. Those girls with their Crayola markers in the library just didn’t know how easy it is to blow a guy.

Meet Thea at my after-school job. Find Ben, who lives in an apartment with Thea and Mike. They are all four years older than I am. Mike knows how to vandalize, and Thea understands me, because she left her own mother a long time ago. The four of us huddle and sigh. Ben is as silent as I am. But somehow, with them, we talk louder. Drink beer and sit cross-legged on the floor watching the sunset mark the window with its well-oiled brush. Realize that smart guys can actually be sexy, and notice how long I can actually keep the light on, and how much I can really say if I don’t have to wonder if we are here just to fool around. I mean, I can do that, right? But then I can have deep sex and love, remember to think about not having one another for-ever, and then get scared–hard scared.

Have sex all the time and let him paint my portrait eighteen times over with two kittens running beneath our feet. Decide that, even though I’m failing, I don’t want to be stuck in high school forever–I don’t want to drop out and get high all the time, and give it all up just like that. Decide to be smart again, like Thea, and roll my own cigarettes and make my own jewelry and spend all fucking afternoon in the bookstore if I want and write letters to anyone who really pisses me off–and tell the men to stop staring and call the school to report Mr. Mitchell. But somehow, despite that, don’t talk to my mother or to Ben about birth control, or say much about the first sexually transmitted disease. Don’t think too far ahead. Remember to not look too close.

Go to the local bar and put money in the jukebox till the whole crowd knows how to overplay “Tupelo Honey.” Don’t think about the girls. Don’t remember Patty. Remember my connection to Thea. Remember how she tells me how lovely I am–so lovely–all the time. Let me hug you. She loved all her girlfriends. They travelled and slept in patchwork quilts; they followed the Pixies even. They were crazy eighties girls. They talked all about their unplanned pregnancies and had abortions without apology. All their mothers were feminists. Just like Thea’s. Just like mine. Remember to pull out the old Ms. book, The Decade of Women, when I get home, and trace my finger across those women again–those activists, those marchers, those fed-up suburban housewives, city workers, and students who said fuck off with just a T-shirt. They wanted equal rights now. Isn’t that what made them all finally walk?

And here I am now, walking too–but still, tied to a guy. Here he is, too, worried about cumming too fast, but not talking about it, or talking anymore about condoms or the Pill, and look at me, not talking about these things either. You wonder why it took a year to get pregnant. Thea says, I will help you.

Ben cowers till he can’t stop cowering. He tells me that he doesn’t want me to keep it. He tells me that he does. He tells me things all the time when he’s not reading Howl or drinking too much wine or threatening to go back to his college across the country now, for good, even though I’ve only just barely graduated high school and started college. He wants me to drop out, then, and move to Seattle. If I love him, then I will love him there. And if I don’t, then I am “chicken.” I convince myself that it’s the “writer’s life”: a crazy messed-up path–or, it’s romance: I can walk blonde dogs and be blonde with a tiny blonde child, too. I can forget the fights and forget the loneliness and forget the books and forget the words–forget Thea, forget ever learning to agitate the world.

I call the clinic like I am joining some inevitable girls-only club. I call also to save my life. Really, I was weaned on choice. This is water to me; it’s part of my birthright. That’s why the women walked, and why I am here, why I fucked up. I had the right to fuck up. I didn’t fuck up that bad; I fucked up bad.

At that first appointment, the doctor comes in to check me. She pushes down on my abdomen with one hand, and puts her fingers inside me with the other. She says, Yes, you are pregnant. She says to make the next appointment as soon as I can.

They counsel me before the procedure. Two women in the room. We sit around an oval wooden table. I am just nineteen, a long time from 1982. Patty is far from West Virginia. The chocolate batter is all dried up. The boys have gone home again; there are just women now. They look at me, but say few words. Ben is there, but he’s not there.

He’s not here, is he? They ask. No. I am.

They tell me it’s my choice, and one that only I can make. They tell me it’s my choice, but it is one I will never forget–and I am here to tell you, that is the truth. The counsellors ask again, Is this what you want to do? I remember to tell them: Yes, this is what I want to do. This is it now; what do you think? I am nineteen years old, I am nineteen years old. I am not going to stay with him. I am not going to drop out of college. I am not going to not get my degree. Do I need to tell you how I just barely made it out of high school?

Ben drives the car the day of the abortion and cries again. He tells me to put his watch on and never take it off. Later, he says that the door that closed behind me was like the spinning-to-lock door of a submarine. He goes down with it. I stay numb.

The doctor’s heels click on the linoleum floor. She says nothing to me. She aborts it quickly. It goes into that glass jar. Thea tells me later that the same thought I had had occurred to her–it is done and it cannot be undone. That is the choice, in black and white. That is the choice I made. That is the choice she made. The girlfriends know how to tell one another the stories–and I walk back home to her, so she can tell me everything.

We sit and talk in her bed till the sun pushes another October day into sunrise, and she works her fingers over two thin needles with indigo wool. I go back to college and forget about Ben in stages. He kicks a hole in his painting of me with a pregnant belly and dumps our sand-sculpture-in-a-bottle all over the floor. I start a women’s group and manage a campus magazine with story after story of feminist pride. I promise myself many things, but she was right: I did not ever forget.

Sometimes I still think of Patty and the freckles all up and down her legs. How many times did we lie there all quiet? Not a peep anywhere, from anyone. No one’s hands on us, nobody’s tongue–nothing to think about, really, except ourselves. That’s how I always remember it. I don’t even know now where she is–but I tell you, I know that I’m still here.

With She’s Shameless, co-editors Megan Griffith-Greene and Stacey May Fowles have compiled an anthology of fearless and funny non-fiction about strong, smart and shameless women. With wit and honesty, the writers share stories of their teen experiences (both positive and negative) on everything from pop culture to high school principals. The book is founded on Shameless magazine’s tradition of smart, sassy, honest and inclusive writing, and reaches out to young female readers who are often ignored by mainstream: freethinkers, queer youth, young women of colour, punk rockers, feminists, intellectuals, artists, and activists. Join us for the launch on June 23rd.

Please Note: Due to the personal nature of the She’s Shameless stories, comments will be closed for these posts. Thank you for your understanding.