In the Blog

Gender, Race and Autism

Illustration Saul Freedman-Lawson

I have always been separate from others. When I was little, I was content to melt into the corner with a peanut butter sandwich in one hand and a book in the other, oblivious to the intricate lives of others around me, content to be on my own. However, as I got older, I began to watch other kids my age more - I noticed girls talking together about the latest episode of Hannah Montana, boys talking about playing soccer at lunch, and even the quiet ones like me talking at lunch in little groups. I never had friends, never really talked to people in my class, but never really knew why. The insistent thought in my head telling me that I didn’t operate like everyone else became louder and louder.

Years later, I realized I meet most of the criteria for Aspergers as agreed upon by doctors: obsessive and singular fixation on certain interests, trouble with looking people in the eye during conversation, an aversion to crowds and certain food textures, and a major lack of natural social skills. However, I was never diagnosed - and that’s not surprising. My case is like many others: many girls and/or people of colour fall through the medical cracks. According to a Canadian study, the diagnosis rate for boys with autism is 1 in 42. The rate for girls is 1 in 189. It is also true that white children are 30% more likely to get diagnosed than black children and 50% more likely to get diagnosed than Latino children American Academy of Pediatrics. First Nations children are so underrepresented in research that viable statistics for them don’t exist (source). These findings don’t necessarily mean that girls and people of colour develop autism less frequently than boys especially white boys. But, rather, it suggests that they aren’t getting diagnosed due to oppressive stereotypes - ensuring that they don’t get necessary treatment and support for Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD).

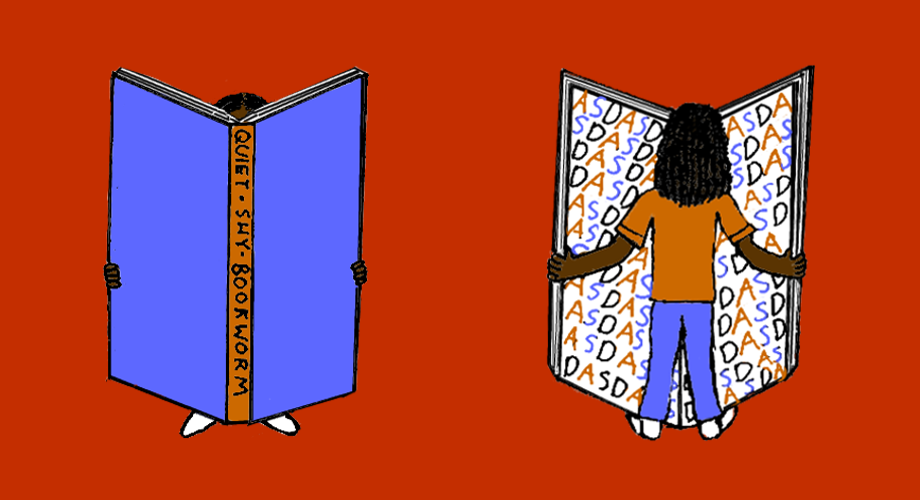

I was (and still am) in love with reading. I didn’t care for learning long division, or playing house with other kids or pretty much anything else - I much preferred performing plays with the_ Little Women_, roaming mystical moors with Poe, or sitting by a common room fire with Hermione Granger. My reading was both a source of entertainment and a way to comfortably connect with the outside world. It became obsessive - I read before school, during school, at lunch, after school, before dinner, after dinner, before bed, and even sometimes through the whole night. However, this didn’t strike anyone as bizarre. It is somewhat normal for girls to be shy, quiet bookworms. Because it didn’t fit the typical set of obsessions that people with ASD usually have (what are known as “special interests”), it didn’t raise any questions about possible ASD. We all know the stereotype - boys with ASD fixating on things like outer space, trains, cars, math, and dinosaurs. These are all habits that parents and doctors are conditioned to look for when it comes to diagnosing ASD. They are all typically “masculine” interests/activities. That’s why my obsession with reading never raised any alarms - it doesn’t fit into the set of special interests that are deemed masculine and therefore related to ASD.

Part of the reason why girls are diagnosed less often is because many are fixated on femininely-coded things such as the humanities, Disney movies, fashion, art and/or dance, or in my case, reading. YouTuber MindOfHerOwn, a late diagnosed woman with Aspergers, has said that “it was hard for the doctor to diagnose [her]” because her special interests include geography, other cultures, and languages. Because her interests are more anthropological and less like the stereotypical hard sciences, she wasn’t diagnosed with ASD until her late forties. Special interests are masculinely-coded because most of the research and results that many doctors use in order to recognize ASD in children are by and for boys. Researchers and doctors don’t take into account the fact that many diagnostic signs, like special interests, present differently in girls. The male-heavy research and subsequent stereotyping of signs keeps girls and women from getting diagnosed and prolongs the specialized support that they with ASD may need.

I remember when I was in middle school, I told my doctor I thought I was on the spectrum. I think that I told her that when I was younger, I never had friends. I wasn’t given much of a chance to explain more when she told me I was just introverted. I knew that I was introverted, and that she was a medical professional that I trusted, so I believed her and dropped the idea. Now that I’m seeking a diagnosis again I can better articulate my experiences, but my doctor doubted me because of a pervasive underestimation or misdiagnosis of ASD symptoms in women. It was found that in most cases, in order for women to be diagnosed with anything on the spectrum, it seemed that they had to “have low IQs and extreme behaviour problems.” This represents an extreme end of the spectrum and the severe symptoms that can’t be explained away or ignored. However, girls that are high-functioning are almost completely looked over, or their parents are told to “watch and wait”, or they are given a different diagnosis like OCD or ADHD.

The underestimation or misdiagnosis of symptoms also occurs with people of colour. Because of the stereotype that young boys of colour, especially black boys, are bad-tempered and troublemakers, ASD can be misdiagnosed as psychosis, an anger control problem, or it can even be seen as just “bad behaviour.” Even when parents know it’s not any of those things, it can be hard to get doctors to believe that it might be ASD for children of colour because of racially charged stereotypes. Shaquana Newsom-Battle, the mother of Major, an African American boy on the low end of the spectrum, said that she had to go to four different medical professionals to get a diagnosis. Despite his underdevelopment in speech and aversion to change, textures, and certain foods, doctors didn’t believe that he could have ASD. Just like girls aren’t as likely to be diagnosed because all the research is mainly conducted on boys with ASD, people of colour aren’t as likely to be diagnosed because most or all of the boys in research studies are white. Due to biases within the medical community, children of colour are not believed and therefore not diagnosed when it comes to ASD - keeping them from getting accommodations from parents, doctors, and teachers.

Another huge reason why children of colour do not get diagnosed is because many of their parents don’t have the resources to recognize ASD and to seek diagnosis. 22% of all non-Aboriginal people of colour living in Canada and 60% of all First Nations children on reserve live in poverty. Lower socioeconomic status means lower health literacy, access to education, and quality care. Many parents don’t know the signs, and when given a misdiagnosis, don’t question it. It’s not their fault they don’t have information on recognizing ASD, but keeping parents from lower socioeconomic statuses in the dark will continue to be detrimental for their kids. It’s necessary to disseminate more information on recognizing ASD so that all kids on the spectrum can receive the help that they may need.

When I first told my parents about knowing I was on the spectrum, I benefitted from the fact that my mother is, as well. They believed me and knew that it wasn’t necessarily a bad thing that I was different than most kids. However, for many kids, familial culture can also hinder support, especially in West and Southeast Asian households. According to Melody Cao, the parents of Chinese children feel so responsible for their children’s health that “parents who have a child with mental health problems often go to see their doctors with guilt and shame, thinking their children’s illness is their own fault.” Gowri Kobikrishna, who has a seventeen-year-old son with autism, said that “In our community, they [were] not going to accept him as one of their family, so that’s why we were scared to go out and tell that we have a son with autism.” There is still a stigma, both from within the family and as well as the broader community, that devalues and demonizes the lives of those with ASD, keeping them from acceptance and support.

Increased diagnosis can definitely be a bad thing. For example, the overdiagnosis of ADHD in kids is becoming an increasing problem because of the limited resources for those affected and the the overprescription of stimulants. It’s important to keep in mind that not all antisocial kids have ASD. However, I am advocating for the increase of diagnosis for girls and/or kids of colour because we are overlooked. We deserve the same representation in research, the same support, the same treatment if we need it. We deserve to be seen.

In spite of everything, it’s a good era for people with ASD. Even in the past seven years, diagnoses have doubled. Adults with ASD are coming together and sharing their experiences, and supporting each other online. There are fewer stigmas now than there used to be - I am writing this unafraid of what people may think of me because I truly believe that they won’t be particularly bothered by the fact that I’m on the spectrum. However, despite the fact that many of us live in shadowy limbo without diagnosis, this is an important era for us because we are actually talking about the reasons why we’re there. Countless members of our community have pointed out, just like I have, the disparities of diagnosis that keep us from accessing necessary accommodation. Because people with ASD and researchers have opened up a dialogue about the problems we face, more research is being done on why we’re overlooked. More doctors are recognizing the disparities and are looking more closely at girls and/or minorities. We still have a long way to come, but we can look to the near future and see the best ahead.