In the Blog

Interrupting Our Ways: violence prevention and intervention

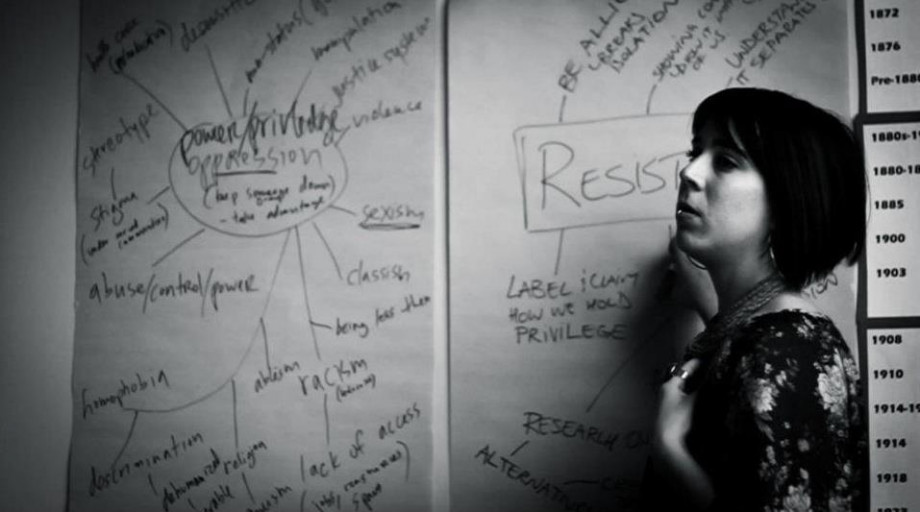

ReAct, Respect in Action, is a youth education violence prevention group. All of the workshops, groups and discussions we facilitate with young people, we do to listen to and validate the experiences of violence youth have had and we do so with the hope of preventing future violence. But over the past couple of years the ReAct team has started asking the question: what happens after violence? While continuing with the goal of prevention, we have also made more space in our program and workshops to discuss what young people can do when they survive violence. We’ve created new materials and workshops that focus on care, supporting friends, and healing justice - a kind of justice that isn’t about punishment, but about responsibility, community involvement and transformation. We’ve asked other young people what these ideas mean to them and have been told that the work of healing ourselves and our communities is powerful and much-needed.

Recently, the ReAct team was blown away by The Interrupters, a documentary about youth workers in Chicago doing on-the-ground violence-intervention work. If there ever was a picture of “frontline youth work” in the dictionary, this team would be it. The interrupters step in - I mean right into it - breaking up fights, making speeches at funerals about ending the violence (“cease the fire”), stopping people from going after revenge, supporting mothers and families when they lose someone to violence, and physically staying with people so they stay safe (“the violence interrupters have one goal in mind: save a life”).

Referring to social injustices as a root of youth violence, one of the interrupters says, “when you feel ostracized by the society, you try to dominate your own surroundings.” I hope our workshops help young people name those realities and root causes - that it makes sense to feel angry at the world because of harassment, oppression, being treated as “less than,” witnessing people you love die unjustly, and all the other injustices that happen. But I also hope that youth can recognize that it isn’t okay to take it out on each other by abusing and stepping on those around us. Doing that doesn’t make your life better or make the pain go away. In the end, it all comes full circle, as things tend to do.

While designing some new workshops about youth justice, I learned about an Indigenous community in Manitoba: Hollow Water. It is a community that, like hundreds of others, continues to struggle and survive through the devastating effects of colonialism and residential schools. In the 1980s, sexual abuse was affecting almost every person in the community and no one was talking about it; then a small group of people broke the silence. They created spaces for adults, youth and children to address the abuse they had or were experiencing. They quickly saw that in order to deal with abuse youth were experiencing in the present, they had to heal generations of past wounds. To stop further violence from happening, they had to recognize that people were holding generations of trauma in their hearts and bodies. Through a holistic approach of working outside of the criminal justice system with everyone involved (“offenders”, survivors, families and the community), they started doing healing work and transforming the community. They continue to do so today.

There can’t just be one approach to violence prevention; all of these approaches (awareness, education, healing, and intervention) are necessary and most effective when used together.

May is Sexual Assault Prevention Month, and after watching The Interrupters and learning about Hollow Water, I’ve been thinking about what preventing sexual violence means. Does it mean raising awareness about consent, expanding the generally accepted narrow definition of sexual violence, and highlighting the facts about who experiences the most violence? Yes. Does it mean advocating for survivors of violence to be listened to, believed, and supported? Yes. But it also means talking about the hard-to-accept fact that this violence is all around us, that people we love are perpetrating it, and that we need to find ways to interrupt this violence in our communities.

This month (and for that matter every month because I’m a bit tired of only one month being given to recognizing our histories and experiences), I want to prevent sexual assault by working in my community to build a culture that doesn’t tolerate it. In ReAct programs, we will continue to discuss practices of community accountability and what role we, as an anti-violence group, can play in it. In order to prevent violence, we must address it both at its roots and its daily impacts. And when we fall short of annihilating it at its roots we must also explore ways of interrupting it when it happens in our streets, homes, schools and community centers.

The AMY Project (http://www.theamyproject.com/)

Keli Bellaire has coordinated METRAC’s youth anti-violence peer-education program, “ReAct: Respect in Action.” Using popular education frameworks, she has been facilitating workshops and youth groups for 8 years in Halifax, Toronto and throughout southern Ontario. Keli grounds her workshops in participants’ knowledge, recognizing people’s lived experiences as expertise. She believes in education as a practice of social transformation and freedom: liberating our minds from the boxes we’ve been taught to live in and taking action to build a just world. She has long been part of anti-poverty, feminist and queer rights movements and works in solidarity with community groups for justice in Palestine and Indigenous Sovereignty.